Making sense of all the continuous practices

The flood of continuous practices and jargon around the new ways of working can be unnerving to new teams, here’s a simplification attempt.

The last four years have witnessed remarkable changes in the way we perform most of the post-development tasks in a typical Agile methodology-based software development. And with the excitement also comes confusion of not just the why, but what? and how? too. In this blog post, I’ll try to break down the continuous cycle and re-assemble(based on my experience) to help readers make sense of it.

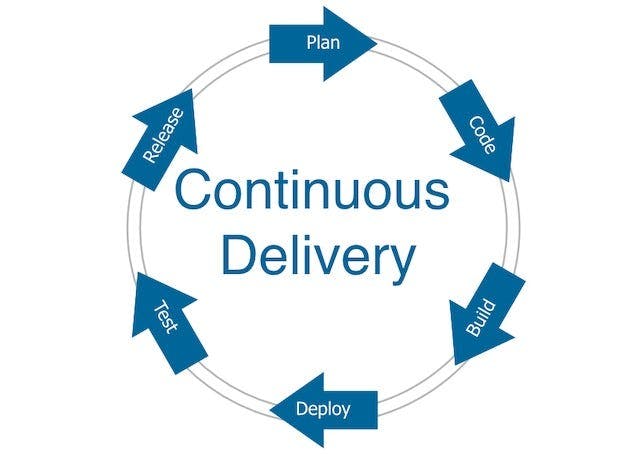

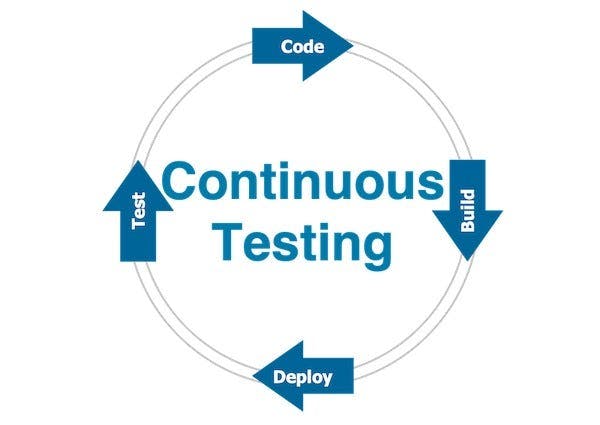

If I had to put it in one diagram “Continuous Delivery” would essentially look like this

Continuous Delivery Cycle

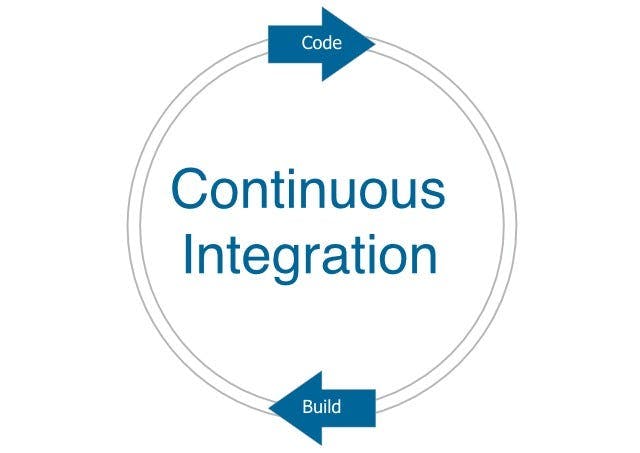

As novel as it may seem, I agree it is quite hard to figure out what the implementation would look like. So let’s start creating some pictures (worth a thousand words) to see what the typical continuous delivery cycle is made up of. Let's look at the two steps Code & Build. These two continual cycles are what we call Continuous Integration.

Continuous Integration is a software development practice where members of a team integrate their work frequently, usually each person integrates at least daily — leading to multiple integrations per day. Each integration is verified by an automated build (including test) to detect integration errors as quickly as possible. — Martin Fowler

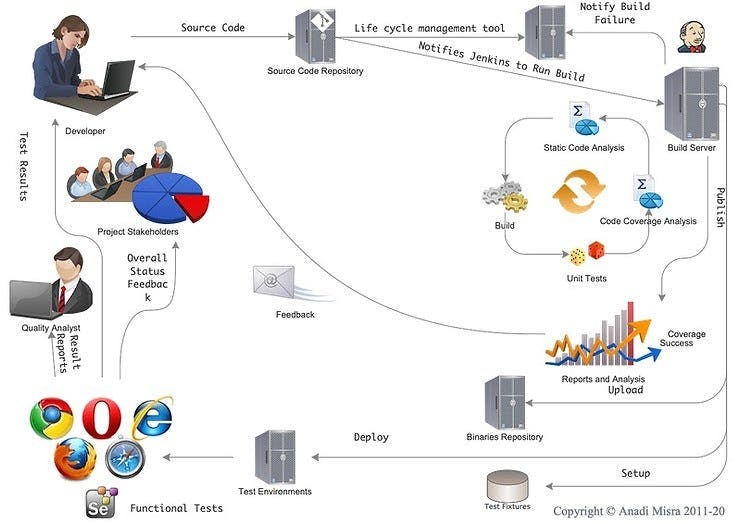

The idea is that we keep the source code in a centralised repository to which all members keep adding their code regularly (at least once a day or even better many times a day in small batches) and this addition of code would trigger a build, including tests. The passing or failure of the build then becomes quick feedback about whether the “new code” has added working functionality to the systems or broken regression (or both ;-) ). Let’s look at a diagram of how our team gets it done here.

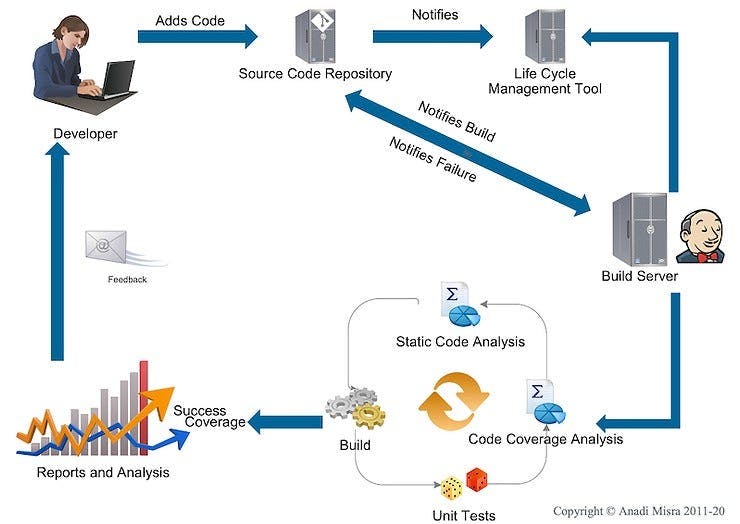

How a continuous integration-based development flow would look like

As you can see there’s quite a bit of “integration” going on to get continuous integration working, we have Git as the Version Control System, a Project/Product Lifecycle Management Tool, Mr. Jenkins and a whole lot of analysis and reports. It’s important to understand the flow nonetheless; which starts in our case as soon as a developer “pushes” code to our Git Repository.

The git repository runs some of it's own checks primarily validating whether comments are in a particular format or not

it then notifies our build server to run a build

It also notifies the life cycle management tool to update revision history and build status to in progress (there’s a radiator view from this ALM which is on display on this floor)

The build, maven on Jenkins in our case runs in four steps, static code analysis using Sonar, we’re using an approach here of failing the build at first error, so this is the first litmus test, confirming code follows a certain coding standard

It then runs the compilation and similar tasks

This is followed by tests, as defined in maven build life cycles, we run unit and “integration tests” here via maven life cycles

The reports from all of these are provided as feedback to the developer and published in the builds dashboard too

In case of failure, our ALM creates a defect and assigns it to the developer, other than letting others know who broke the build

This cycle by itself does solve a lot of issues in terms of keeping the code healthy and ensuring regression hasn’t broken. However, defects don’t just come from bad engineering; they also come due to misunderstanding of features. So we need more than just continuous unit/component/service tests to be sure our product works as expected. Typically what matters is that the users, who would use your system in one or more “flows” are delivered a non-buggy experience. To get to that stage we must ask ourselves after every continuous integration cycle.

Is this enough to put the product in production?

If the answer is no, you start tracing answers to why? from production backwards to your development, you’ll sooner or later come down to one or more of the following activities pending before we can be certain

Functional Regression and Testing of new features

Performance Testing

Security Vulnerabilities

End-to-end use cases to be tested

Configuration, hardening or similar activities etc

So we need to find a way where we could run all of these in continuous cycles, hence comes the word “Continuous Testing” which in my experience is bringing heavy automation to testing to enable running all the above-mentioned tests in a continuous cycle just like build and development. Going by that, we’re simply adding another spoke to our continuous wheel.

Typically you will be creating separate jobs in Jenkins one each for deployment, preparing every kind of test fixture and running these tests. I’d prefer to deploy in parallel to one environment dedicated to each functional, and nonfunctional test case such as security etc., and performance tests and run jobs for the heavier tests in them, stopping any further deployment if any of these tests fail.

Now to get there and be in a position to use all of this you’d need a way to be able to continuously deploy to environments, yup that’s where Continuous Deployment fits in (and keeps itself only to this context); it is the ability to deploy to any target environment in a repeatable, automated manner, ideally with all continuation changes too, at the click of a button. So if I had to explain our previous diagram I’d just highlight one of the places where it is compared to the picture in the continuous cycles.

Even with all of this automation in place, you’d still require manual verification at some stage, we should keep all such steps for the “pre-production” or staging environment IMHO. And finally, deploy to production once all other prerequisites are fulfilled.

You’ll notice I haven’t put in steps related to business processes or planning and budgeting around releases; other than the fact that they cannot be automated; we have to address them in small batches too, that’s like bringing in “Agile” to planning (here I mean beyond the sprint planning) too, or maybe some sort of continuous planning in for example twice a quarter. They have to be addressed nonetheless in a way that fits better with the small batch-paced world of software product development that the world is slowly moving towards when you realise moving these processes to a more “agile” way is when you attain what we showed in the first diagram; Continuous Delivery!

It’s important to realise why we are doing all of this to be able to understand what these practices are and hence build competency to utilise them in your software development lifecycle.

Originally published at anadimisra.com on July 16, 2011.